Perlin noise and simplex noise are the topics I keep coming back to, because I know they form the basis of a lot of procedurally generated content. All I knew about them to start with was give this function a value for 1 to 4 dimensions, and it will return a “random” value that is constant based on the input.

There is a somewhat ambiguous warning about passing integers “might” lead to a constant result. No, it will always be the same value at any integer. Turns out this is fundamental to how noise functions work:

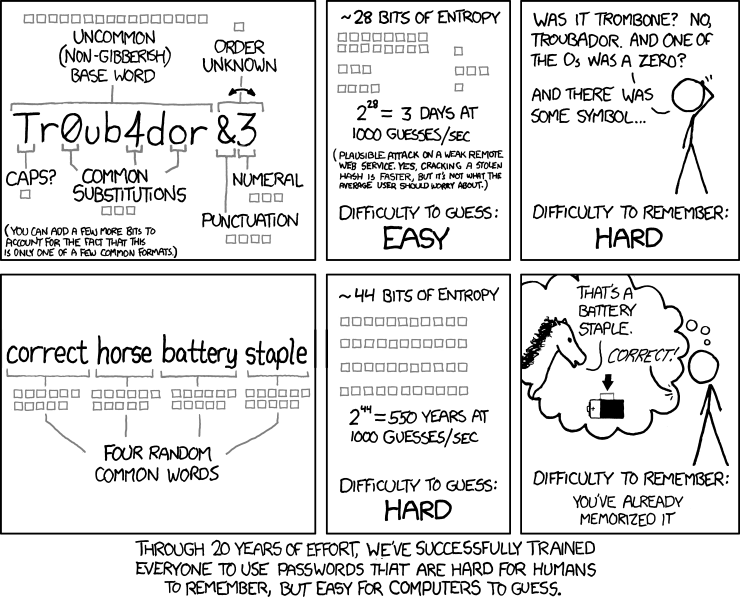

One explanation I’ve read says that Perlin noise is essentially mixing dot products from 4 vectors from neighboring integers to the exact point you’ve chosen and 4 copies of a constant vector present at each of those “corners.” This is represented by the arrows in the above image.

A consequence of the constant vector at every integer value is that any integer will return the exact same value.

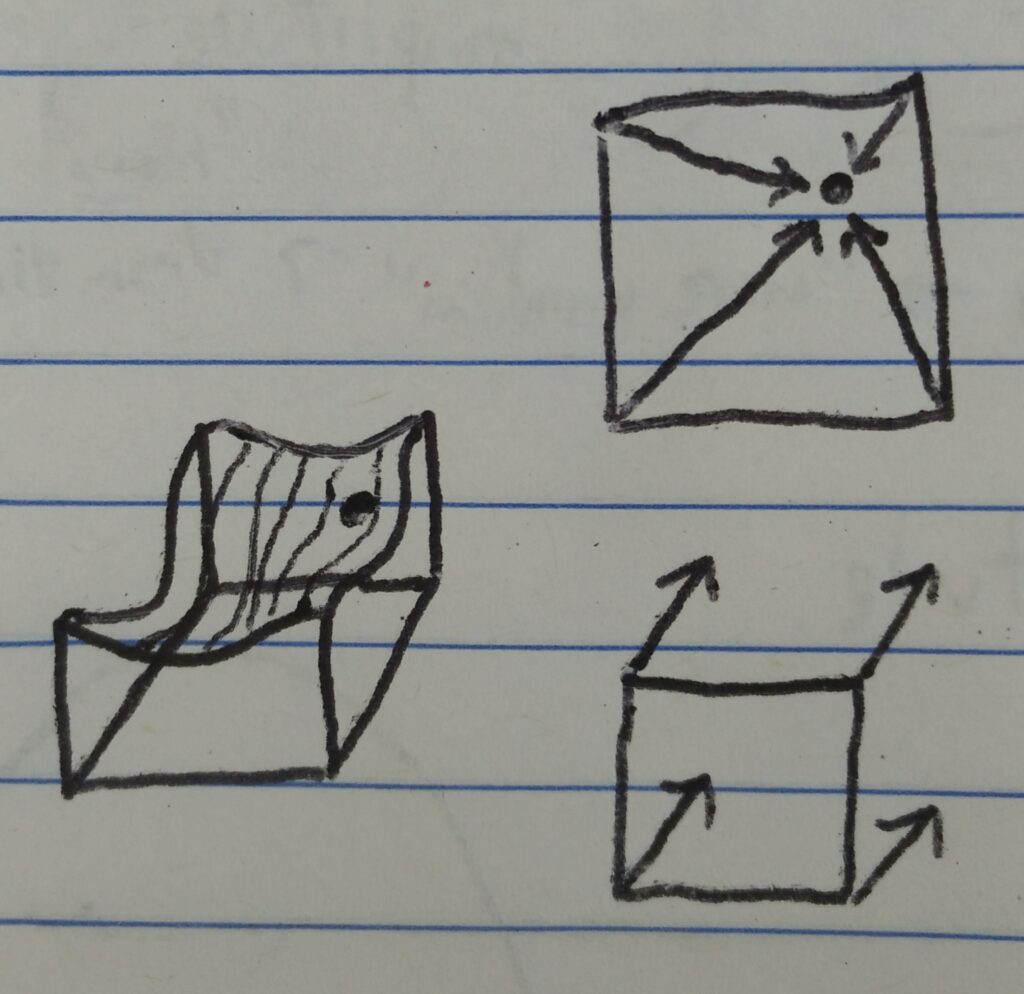

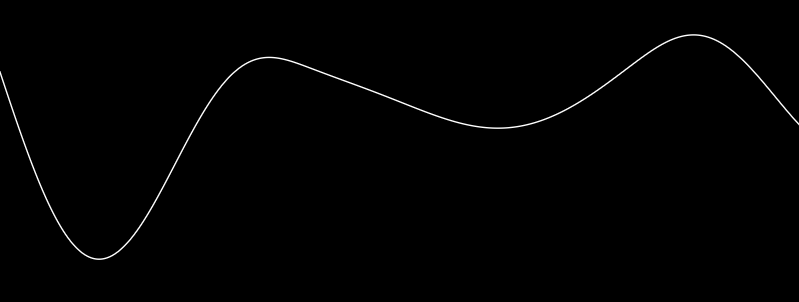

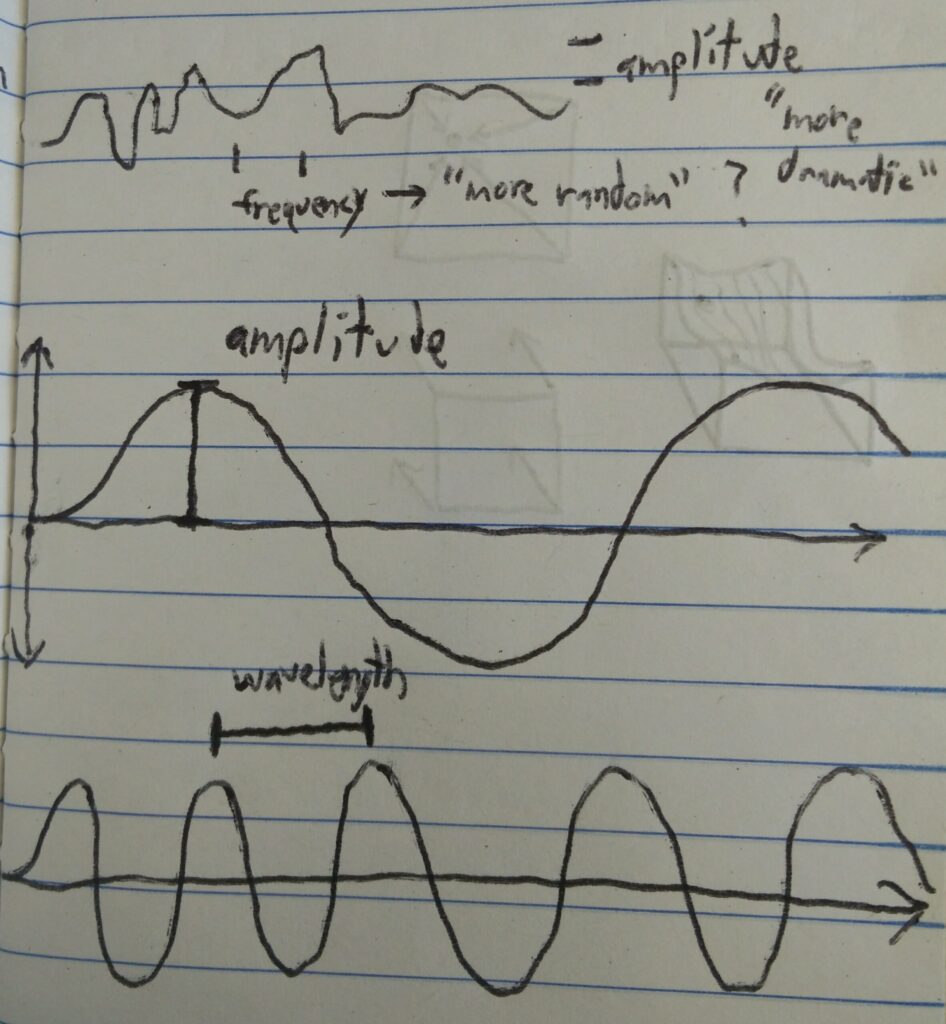

Another explanation describes a noise function as mixed sine functions of differing amplitudes and frequencies. Looking at an output from 1-dimensional noise definitely can make it appear to be that simple, but it isn’t. I mention this idea for three reasons:

- It looks similar. This can help trying to visualize it.

- It is periodic, you do not have an infinite domain of values to choose from without repetition.

- Some terminology can still apply, such as adjusting the frequency or amplitude of noise, and depending on implementation, the range can be the same (or something easy like LÖVE‘s 0 to 1).

Noise Usage

I have been trying to use noise for quite a while, with a lot of failure, mainly around not understanding the domain and range of the noise function. As of now, these are the things I’ve learned:

- Period / Domain: There is a sample of (usually) 256 values used for the constant vectors, this defines the period before the noise function starts repeating. Keep this in mind combined with other adjustments to hide or avoid this repetition. (This is how I discovered the period of LÖVE’s implementation.)

- Frequency: A higher frequency can be achieved by stretching the input, leading to quicker, more dramatic transitions.

- Amplitude: This one feels kind of obvious, but with LÖVE, the output is 0 to 1, so that needs to be mapped to whatever range is desired.

Sources

(Skipping those linked to within the post. Note: All resources are archived using the services linked to on Archives & Sources.)

- /r/proceduralgeneration/ post that led to me revisiting noise today

- A different explanation of Perlin noise

- Relevant experiments with Perlin noise

My apologies, but any other relevant sources at this time have been lost to the ages, with the possible exception of the source code to a demake of No Man’s Sky I have put some work into. I will revisit that at a later date.