This post has had more hours put into it than the majority of my writings here. It still doesn’t feel finished, or correct, because this is a huge topic. I think it’s more useful to publish as-is, and update it with links to more detailed thoughts as I publish those thoughts.

Key Takeaways

- Organization is something to slowly bring in as needed, not something to focus on from the beginning.

- File hierarchy is a losing strategy. If you have to use folders, keep them as simple, organized, and flat as possible.

- Tags should be kept simple. They have most of the flaws of folders.

- Don’t stress about links. Use them, but it’s okay to forget or to remove extra links later.

- Journal entries should be simple and unstructured – easily triaged. Likewise, reviews should be kept simple.

How I Got Here

I don’t have a magic answer that will solve your organization needs, but I have 2,300 notes from as far back as 20071, I’ve been trying to organize them since 2010, and I think I finally am getting the hang of it as of 2 weeks ago. When your interests include everything humanity has ever done – and many things beyond, it gets unwieldy to organize. When you have neurodivergent brain, it gets even harder.

It started with folders – after all, that’s how computer filesystems work – but then you run into at least two distinct problems: “Where did I put that?” and “Where does this go?“. The first can be helped with search, but many search tools are inadequate. The second takes longer to appear, because it only hits you after you’ve decided to put the same kind of file in multiple folders.

Then you move to tags (or categories, which are just stricter tags). Tags allow you to place the same thing in multiple places, solving the most significant problem of folders: hierarchies. Eventually, you run into the same problems in a different form: “What did I tag that with?” and “What do I tag this with?“. You resolve to use tags differently, but then they become too vague to be useful (everything in my journal is tagged #journal) or too specific (I only have a single note about dumbbell fusion reactors, why does that specific concept have its own tag?).

Folders, categories, and tags are all fundamentally the same thing.

They’re like the Dewey decimal system, trying to fit all of possibility into a logically ordered structure. Reality refuses to fit in this box.

Use these sparingly or not at all whenever possible. They limit your ability to organize rather than help it.

It is critical to recognize these similarities and their failings. I used to think tags a superior organizational method, and focused on their usage for years. It all fell apart. (I now think links between notes are the most important organizational method, but only as long as you let them happen naturally. Don’t stress about what should or shouldn’t be linked.)

In 2019, I finally heard of something beyond default “Notes” apps5. I started using Obsidian and trying to follow the Zettelkasten method (every single note must be a single specific idea – an atom). Don’t start like this. It sounds appealing, but it is not for beginners, and it held me back for years. Analysis Paralysis – the inability to make a decision because of the options available – is a trap that I regularly fall into. “Is this note really atomic?” distracts you from the importance of what the note connects to. Similarly, I was distracted by the beauty of the graph, and decided everything must be linked and the graph must be useful. These ideas are misguided.

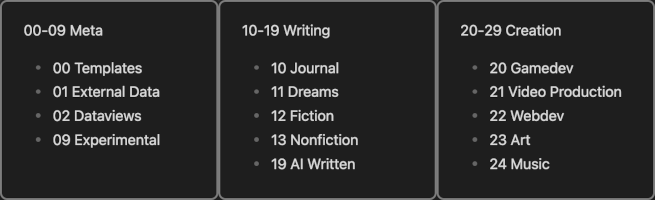

My past 3 years have been spent wandering between notetaking methodologies without solving any of my core problems. I used the Theme System, got lost in LYT‘s MOCs (yes, their website does look like a scam), tried Bullet Journaling, looked at PARA & LATCH, and finally started making real changes after stumbling across the Johnny.Decimal system and watching several videos from Nicole van der Hoeven. I’ve realized for a long time that file structure is pointless2, but a part of my brain obsesses over where files are. Using the simple hierarchy of the Johnny.Decimal system allows me to shut up that part of my brain, while generally avoiding thought on the location of files.

The primary reason this works for me is Obsidian’s settings for where attachments and new files are are placed. Previously I followed the doctrine of having attachments in a specific organized folder, and briefly had all new notes created in the root (so they could be properly organized after creation). That just leads to splitting some files from what they are related to, and creating extra burdens organizing files uselessly.

Ironically, the hardest lesson for me has been to focus less on organization. Organization should not be your first goal. Using your notes effectively is far more important than them being organized. If my notes were perfectly organized, I would have very few and nearly useless notes.

Daily Notes & The Importance of Review

Daily notes are a dumping ground of thoughts, and a place to link with significant notes – creating a loose record of each day. They are for whims. The goal of a daily note should not be aesthetic, organized, or even complete. I recommend embracing the fleeting nature of days – don’t try too hard to complete task lists created in your daily notes, don’t follow a specific format that you’ll end up feeling bogged down in, don’t feel like a note is required for every day.

The organization comes in first with weekly reviews3. Each week, I make a note summarizing the events from the previous week and create a task lists for things more important than daily whims. These I am currently leaving very freeform, just like daily notes. I haven’t done this very much yet, but the flexibility of not trying to follow a standard seems to be helping so far. Usually, some of these tasks end up including how to manage the rest of my notes. This review process is hierarchical, and cyclical. Every month gets its review based on the previous weeks, quarterly reviews for their months, and yearly reviews for those.

Again, I have only just started this process, so I can’t speak to structure in higher levels of review. Maybe it’ll be useful, maybe it won’t be. It’s important to discover what works for you instead of following a prescription.

The Importance of Forgetting

I have an old task list with thousands of items. It’s unapproachable, unusable, downright silly. Every day, I create more incomplete tasks. I used to view this as a flaw to be solved, but now I view it as a feature. If you are completing your todo lists every day, you’re doing something wrong.4 So many tasks I create are not really needed, and with a finite life, I shouldn’t expect to achieve everything I want to.

Likewise, a lot of strategies for organization and usage of notes focus on making sure everything is findable. This is a noble goal, but one that I think acts against the usefulness of notetaking. The majority of the value in notes is writing them in the first place, so forgetting them shouldn’t be a large concern. (And that’s before even considering psychology and physiology. Forgetting is important for health.)

Footnotes

- From text files on Windows XP, to iOS (Apple Notes), RedNotebook Portable, Notepad++, GitHub, Atom, Android/Google Notes (and then Keep).. and finally Obsidian.

- A well-written pro/con list based on file hierarchies.

- I believe I am stealing this idea from a combination of things emphasized by Bullet Journaling, the Theme System, and the Periodic Notes Obsidian plugin.

- I first heard this idea on a recent episode of Cortex, where the importance of the order of a task list was discussed.

- This does include Google Keep, and a Google “Notes” app that briefly existed and has since been memory-holed.

(Note: All resources are archived using the services linked to on Archives & Sources.)